Scaling Python a high level introduction

Disclaimer: I (the author) have attempted to write this from a general open source perspective. However I should mention that I am employed by Anaconda Inc and am a maintainer of a particular library mentioned below, Dask. The reader should keep this bias in mind when consuming the following arguments.

This document outlines three approaches to accelerate Python at a high level:

- Scaling in: using efficient compiled code

- Scaling up: using a single machine effectively in parallel

- Scaling out: using multiple machines effectively in parallel

This is written for someone who has only modest exposure to Python and wants a broad overview.

Motivation

People doing data intensive workloads seem to like Python, and in particular they seem to like libraries like Numpy, Pandas, and Scikit-Learn that combine modern algorithms, efficient code, and intuitive interfaces.

And yet we also hear things like “Python is slow” or “Python doesn’t parallelize well” which seem to be at odds with Python’s popularity. How can these things both be true, especially in today’s Big Data environment? What are the options we have today to accelerate and scale Python and how do we choose between them?

This article describes three classes of options for accelerating and scaling Python code, the common options within each class. It also discusses the pros and cons of each class so that people can make high level decisions that are appropriate for their situation. Where possible we link to other resources that discuss particular libraries in more depth.

Scaling in: Accelerating Python in a single thread

The Python language was not originally designed for speed. It is about 2-5x slower when dealing with text and JSON-like data and 100-1000x slower when dealing with numeric data. If used naively this can slow down analyses, leading both to infrequent iteration on new ideas, and also to analyses on smaller datasets that may integrate less information.

Fortunately, most popular Python packages are written in C and so are generally very fast. Packages like Numpy, Pandas, and Scikit-Learn have Python user interfaces, but all of their internal number crunching code is written in a low-level language that is then compiled for speed. This means that the 100-1000x slowdown you might see from using Pure Python for loops goes away, and you’re left with as much speed as a CPU core is likely to give to you.

To be clear: the numeric Python ecosystem runs at C-speeds.

However, this only works if analysts stay within the Numpy, Pandas, and Scikit-Learn APIs. Unfortunately it is common to see non-expert users write Pure Python code (slow) around Numpy arrays or Pandas dataframes.

for row in my_pandas_dataframe:

if row.customer_name == 'Alice':

row.balance = 100

Even though they are including Pandas dataframes in their code it doesn’t mean that they are using Pandas algorithms backed by fast C code.

This mistake is very common and is the single largest contributor to performance issues that we see in the community.

This isn’t surprising. These libraries take skill to use well and the right way to do something may not be immediately obvious to a new user. In this situation you have two options:

- Learn more about how to solve your problem within the Numpy/Pandas/Scikit-Learn system so that you leverage fast compiled code

- Write fast compiled code yourself

They’re both good options. Lets discuss each separately below:

Learn More

Learning more about these systems is always a good idea. Here are a few good ways to accomplish this objective:

- You can read the documentation online, which is quite thorough

- You can ask peers how to solve problems on Stack Overflow. Often you will find that your question has already been asked by someone else, and you can read their answer immediately.

- You can go to a local PyData conference, of which there are dozens both within the US and around the world. These almost always have tutorials on using these libraries efficiently.

- If you work at a company you can hire a professional trainer to come and deliver a course

Python Tools to write compiled code

So you have some pure Python code (slow) and you want to compile it to run more quickly. Your use case is special enough that you don’t expect to find it as a canned algorithm in one of the libraries mentioned above. There are several options. Lets mention a few of the more popular ones:

-

You can write normal C/C++/Fortran code and link it to Python.

In this case you should look at cffi, Cython, ctypes (C), pybind (C++), and f2py (Fortran).

-

You can write in a compiled variant of Python, called Cython: http://cython.org/

This allows you to modify your code only slightly to achieve C speeds if you are careful. Many of the major libraries like Pandas and Scikit-Learn use Cython extensively, so you’ll be in good company. There are several online resources for how to do this well.

I recommend this tutorial by Kurt Smith.

-

You can continue to write Python code, but compile it with Numba: http://numba.pydata.org/

This allows you to keep writing normal Python code, but add a small decorator

@numba.jit def sum(x): total = 0 for i in range(len(x)): total += x[i] return totalNumba is generally the easiest to write in (unless you already prefer C/C++), the easiest to link to Python (you just include it in your normal file), and usually gives the best performance. However it’s also newer and less established in the community. Also, the underlying technology, LLVM, is less well understood than Cython’s C backend, and so debugging issues may be more difficult.

I recommend this tutorial by Gil Forsyth and Lorena Barba.

Costs and Benefits

You should always spend some time scaling in before moving on. The benefits here are often the greatest and there is rarely any administrative cost. I strongly recommend profiling and tuning your code before trying to scale your code to parallel systems.

Writing more efficient code can also help with big data problems. Storing data efficiently can often reduce your memory load by an order of magnitude.

Scaling Up: Using multi-core laptops

After tuning code you may find that an analysis still runs slowly, or that when you try it on a larger dataset you run out of memory. Before you switch to using a massively parallel cluster you may first want to try parallelizing on a single machine. This is often a more productive choice.

When you start working with larger datasets or doing heavier computations, such as might arise from training complex machine learning models, you may find that parallelizing your code to run on multiple cores accelerates your innovative process. By using parallel hardware effectively you can tackle larger problems in less time, leading to achieving better results more quickly. Today people often jump from single-core execution on their laptop to massively parallel execution on a distributed cluster. This skips a couple steps that are often a more productive choice:

- Multi-core and larger-than-memory computation on a personal laptop

- Multi-core execution on a heavy-duty workstation

In this section we’ll cover laptops, mostly from a perspective of user convenience. In the next section we’ll cover heavy workstations, which are sometimes big enough to replace the need for a full cluster.

Multi-core execution on laptops: the benefits of convenience

Modern processors found in consumer grade laptops have somewhere between four and eight cores, of which most programs typically use only one. I recommend that people start parallelizing on their laptop before moving to a cluster for the following reasons:

- It is the easiest choice.

-

It is the most comfortable choice.

You have greater control over the software and development environment on your laptop, and so can iterate more quickly.

- You can use these 4-8 cores in your office, in transit, in a coffee shop, or at home, without the administrative hassles of interacting with any remote or shared system.

-

By writing parallel code on your laptop you learn many of the techniques for writing parallel code on the cluster, but in a more intimate environment that accelerates learning.

It is easier to become a parallel computing expert on your own machine. You will spend more time with it and not be blocked from progress by IT or other external factors.

Python Tools

Common tools in Python for local parallel processing include the following:

- The multiprocessing module or the newer concurrent.futures module. Multiprocessing has been around for longer and is more commonly used, but concurrent.futures is now standard among developers and is the recommended approach for new users. They are functionally equivalent for common cases, but concurrent.futures allows for some more advanced workflows.

- Most cluster-focused tools can also run sensibly on a single machine. These include Spark, Dask, and IPython Parallel, to name a few.

- Some libraries like Scikit-Learn have built their own systems for parallel computing. You should always check the documentation on how a project recommends handling multi-core scaling.

Larger-than-memory execution on laptops

The many cores on your laptop don’t help if your data doesn’t fit in memory. Fortunately, modern fast hard drives do.

A high-end laptop in 2018 has around 32GB of memory. This is the size of a database table with forty columns and 100 million rows. Many companies’ data fits into this space. Or, even if the entire database doesn’t fit, the working set that people tend to deal with does.

However, if this isn’t the case, and the common working set is larger than main memory, then popular libraries like Numpy, Pandas, and Scikit-Learn may start to complain.

Fortunately this is where fast modern hard drives come in. Hard drive technology has changed a lot in the last few years. Aside from GPUs it is probably the single largest recent change of consumer-grade computational technology, reaching 1-2GB/s bandwidth. For many computational analyses, like machine learning, modern flash-based hard drives are fast enough that you can read data from them as fast as your CPUs can process that data. This means that the effective capacity for your computation changes from 32GB of memory, to a terabyte of fast disk space.

Combined with modern storage formats like Parquet an analyst using the right tools can manipulate “Big” datasets comfortably on their laptop.

This does require some special care, and you can’t just use Pandas as normal. But the techniques used in parallel computing will also make it easy to read data from disk in an incremental fashion. Libraries like Spark or Dask mentioned above can help.

Scaling Up: Large Workstations

Sometimes a laptop just isn’t enough, even if well used.

Your analysis requires an order of magnitude more computation or memory than a modern laptop can provide. You might consider scaling up further to a single heavy workstation, before you scale out to a distributed system.

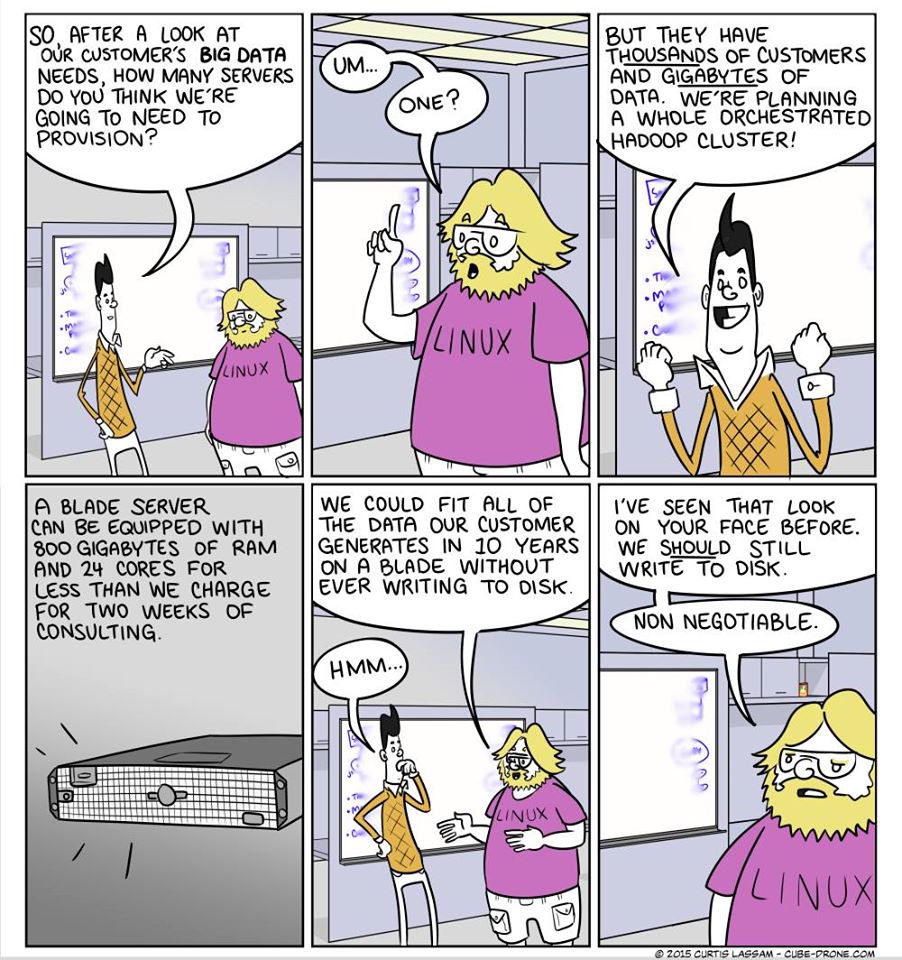

The comic above, while illustrative of a point, is also a few years out of date. In early 2018 blade servers can have upwards of 100 cores and several terabytes of memory. A system like this combines many of the convenience benefits of a personal laptop with many of the performance benefits of a distributed system, making it a good choice for analytic groups doing exploratory work on large datasets. Let’s consider some Pros and Cons of this approach:

Pros:

- Has orders of magnitude more computational power and memory than a laptop

- Is easy to use because it still has a single environment that a user can often control directly

- Is familiar to program because it looks just like a laptop, only bigger

- Is easy for users to log into and share work

- Is often separate from production so that users can experiment more freely

- Does not suffer from the network costs of distributed systems, so often out-performs distributed systems up to a certain data size

Cons:

- This approach doesn’t scale to the 100TB range

- These systems tend to be more personal and so

- They may not have as easy access to a shared data lake

- They may not be shared between all members of a company

- They may not abide by strict software environment standards

- These machines can fail, and so should not be entrusted to mission-critical services

This set of pros and cons make large workstations a common choice for research or analytics groups. Most machine learning groups in universities or research labs share such a machine within the group. Large workstations have also been the platform of choice for the highly competitive finance industry for years.

This isn’t where you want to run your critical work though. This is a very effective environment for exploratory data science.

Python Tools

See the section above for laptops. The tools are the same.

Scaling Out

You can also scale out to parallelize across many machines. This provides the most scalability, but also introduces new challenges and opportunities.

If you will excuse the analogy, scaling out to distributed computing is a bit like this video of Amish farmers raising a barn:

Given a large project (like raising a barn) you break it down into many manageable pieces (like “nail these boards together”, “lift this roofing panel”, or “sand down this edge”). You take stock of however may workers come to help that day (some may be busy and some many have brought extra hands) and assign these tasks to those workers according to the workers’ skills, dependencies between tasks (need to build the roof before you raise the roofing panels), and other constraints that may arise unexpectedly (like injuries, rain, or daylight hours).

This is exactly how distributed computational systems work, except that now the barn is a large and complex computation, the tasks are now smaller in-memory computations that can be handled by a single Python process, and the workers are now computers in your cluster provided by some resource manager (like Yarn or Kubernetes).

As any experienced foreman will tell you, there are Pros and Cons to working with a large team of workers:

Pros

- You can leverage many more workers to achieve your goals

- If workers are unexpectedly removed from service that’s ok, you can fill in with others

- Those same workers can shift between different projects in a predictable way, as mediated by a resource manager

Cons

- You need to break up your project intelligently into many small tasks

- You need a foreman that can allocate those tasks intelligently to workers according to their abilities

- There will be some excess costs in coordination, even if you do the above steps exceedingly well

Distributed systems like Spark, Dask, or SQL databases are intended to handle the first two cons for you. They are not perfect though and there is always a bit of havoc, even with the best run crew.

Dropping the barn analogy for a bit, there are some more concrete challenges:

- You will need to find a way for your users to control their software environment across the cluster. For example they might want a very specific version of Scikit-Learn or Pandas.

- Inter-worker communication costs can dominate some workloads, limiting the kinds of computations that you can run. No distributed system, no matter what it promises, actually gives you a “seamless experience” on a cluster.

- Your distributed system (the foreman) will limit the kinds of algorithms that you can encode. Internally they all have limitations on the level of coordination between workers that they can handle.

These limitations are not always immediately obvious, especially to someone thinking about the high level picture. Expert analysts within the group are likely to have some idea on the kinds of computations that are common within the group and the kinds of computations that particular distributed computational systems are able to run. Their advice may be crucial during this process.

All of the above

The three options above are complimentary and should be overlapped. You can write efficient compiled code that scales up onto multi-core CPUs and scales out onto distributed systems.

Most analyses start on small datasets on a laptop and eventually grow to run on a distributed system after which they come back down to a laptop for refinement. For long-term productivity it is important to have a good handle on the many platforms and stages through which a computation will pass as it evolves.

blog comments powered by Disqus